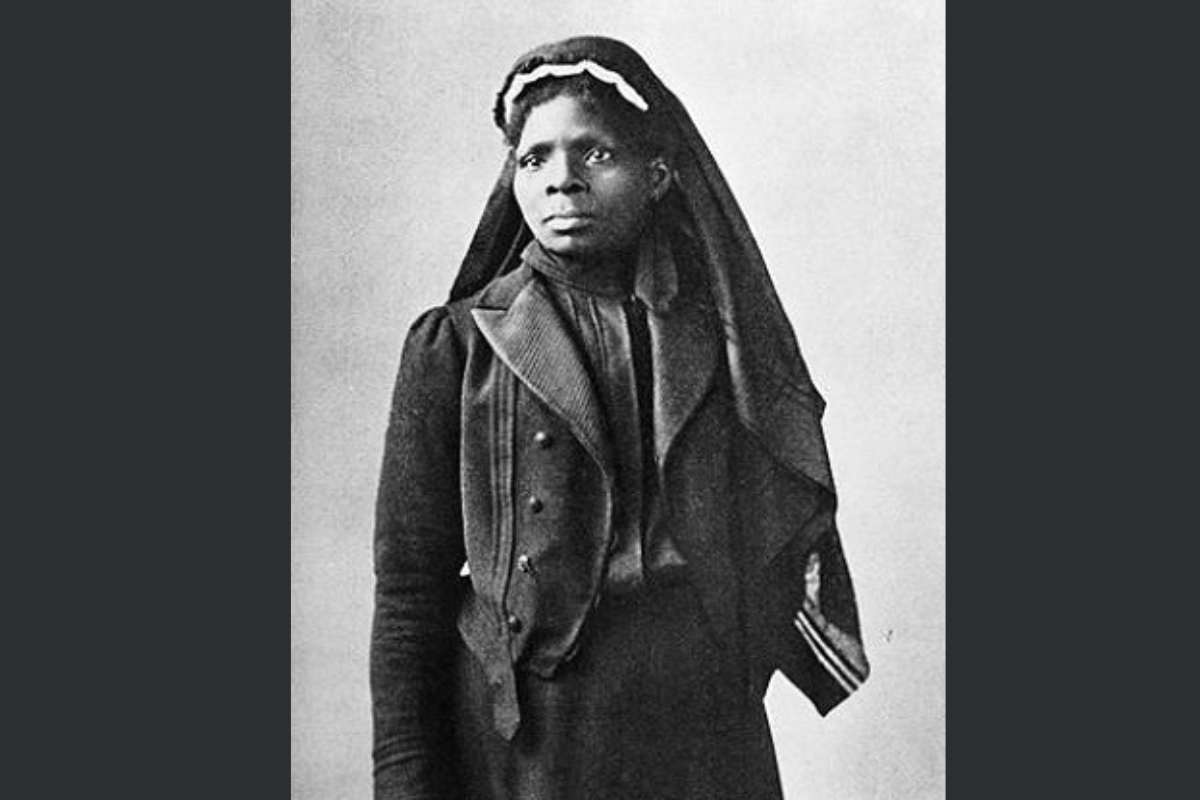

Nurses to Know: Susie King Taylor, the First African-American Army Nurse

Who was Susie King Taylor? Taylor is known as the first African American Army Nurse, but she was also an author and educator. Her writing captured firsthand experiences of the Antebellum South, as well as post-Civil War America. Learn about how Susie King Taylor’s quotes paint a vivid picture of her war service and life.

The Life of Susie King Taylor

An Eventful Childhood

Born August 6, 1848, into slavery, Susie Baker was one of eight siblings. She was raised in Liberty County, Georgia, until the age of 7 when she was moved to Savannah to live with her grandmother, who encouraged her to learn reading and writing skills. Georgia forbade education for enslaved and freed Black children, so Taylor attended secret schools under the tutelage of family friends and freed women.

When Taylor was 13, in 1861, the Civil War broke out, and the next year she moved back to Liberty County as tensions in Savannah grew. In April of 1862, Union forces arrived in an attack at Fort Pulaski. In the skirmish, Taylor and her family were able to escape, fleeing to St. Catherine’s Island, where they boarded the USS Potomska bound for St. Simons Island.

The ship commander, Lieutenant Pendleton G. Watmough, noticed Taylor’s skills of reading, writing, and sewing. Upon arrival in St. Simon’s, he arranged a teaching position for Taylor. At only 14 years old, she taught freed children by day and adults by night. She stayed there for several months before moving to Beaufort, South Carolina, where she joined one of the first African American regiments of the Union Army.

First African American Army Nurse

Women in the 1st South Carolina Volunteers Regiment were mostly given domestic and aid duties. Among them was Harriet Tubman, who served as spy, scout, and nurse. Taylor was a laundress, but she also maintained firearms, taught, and served as a nurse, treating soldiers and civilians with smallpox, cholera, malaria, measles, typhoid, and more.

Taylor credited the smallpox vaccine and sassafras tea for keeping her healthy. During her time in Beaufort, Taylor met fellow Civil War nurse Clara Barton, founder of the Red Cross. She also met and married her first husband, Sergeant Edward King.

In January of 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, freeing enslaved people in Confederate states, and African American infantry units like the 1st Regiment gained formal recognition. In her memoir, Taylor wrote, “It was a glorious day for us all, and we enjoyed every minute of it … many, no doubt, dreamt of this memorable day.”

But the work was far from over: Within a few months, the 1st Regiment was ordered to march to Florida, where they were ambushed by Confederates in blackface. Taylor saw many men die. In 1864, while stationed near Fort Wagner, she witnessed a massive clash with Confederate forces and later wrote about the carnage: “Outside of the fort were many skulls lying about; I have often moved them one side out of the path.”

Later that year, Taylor nearly lost her life when her ship, bound for Hilton Head Island, capsized. She wrote of the event, “Just when we gave up all hope, and in the last moment (as we thought) gave one more despairing cry, we were heard … They found us at last, nearly dead from exposure.”

As the war dragged on, the company encountered fewer Confederate forces, but bitter white Southerners continued to harass and attack them. While marching from Georgia to South Carolina, the company was ambushed by rebels hiding in bushes and shooting at them. Rebels would also hide in Union transportation equipment, waiting for Union soldiers to fall asleep before killing them.

Finally, the company was mustered out, or officially discharged from service, in January 1866. In his parting words, Col. Charles T. Trowbridge stated, “The nation guarantees to you full protection and justice … To the officers of the regiment I would say, your toils are ended, your mission is fulfilled, and we separate forever.”

Post-War Life

Unlike white veterans, Taylor and her husband didn’t receive a pension for their invaluable work during the war effort, and post-war life in the South remained dangerous for African Americans. Tragically, Edward King died after a docking accident in September 1866, a few months before Taylor gave birth to their first child.

Hoping to continue teaching, Taylor opened several schools, but couldn’t support herself in competition with the new public schools in the area. She later worked as a domestic servant, but still wrote that her “interest in the boys in blue had not abated.”

While she and other African Americans were essential to the Union effort, they didn’t experience true freedom in post-war America. The 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments abolished slavery and gave some rights to African Americans, but these were not always honored. Slavery ended, but a new era of prejudice and racism took its place. In her memoir, Taylor wrote:

“I wonder if our white fellow men realize the true sense or meaning of brotherhood? For two hundred years we had toiled for them; the war of 1861 came and was ended, and we thought our race was forever freed from bondage, and that the two races could live in unity with each other, but when we read almost every day of what is being done to my race by some whites in the South, I sometimes ask, ‘Was the war in vain? Has it brought freedom, in the full sense of the word, or has it not made our condition more hopeless?'”

Taylor moved to Boston in 1872, where she married her second husband, Russell L. Taylor, in 1879. She writes of the North, “Here is found liberty in the full sense of the word, liberty for the stranger within her gates, irrespective of race or creed, liberty and justice for all.”

Still, in visits to the Jim Crow South, she witnessed the ongoing horrors for African Americans there. Lynchings, murders, and injustices were common and terrifying. Taylor wrote, “In this ‘land of the free’ we are burned, tortured, and denied a fair trial, murdered for any imaginary wrong conceived in the brain of the negro-hating white man.”

In Boston, Taylor continued her lifelong dedication to service. She became actively involved in veterans’ support, helping organize Women’s Relief Corps #67, an auxiliary group for Civil War veterans that provided fellowship and assistance to aging soldiers.

Despite her bravery and numerous contributions during the war, Taylor’s service was unacknowledged until she published her own memoir in 1902, Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops Late 1st S.C. Volunteers. It remains the only Civil War memoir written by an African American woman about her personal wartime experiences.

Susie King Taylor died in October of 1912 and was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery near Boston.

Lasting Impact

Taylor’s wartime experience was impressive; she was present with troops during battles, cared for the ill and injured in camps and makeshift hospitals, and worked alongside other nurses and volunteers. Her service and sacrifice reflect the essential but often overlooked contributions of Black women in the Union war effort.

Susie King Taylor is an inspiring nurse with a powerful story. If you’re looking for more information on historical figures is nursing, check out our articles on these leaders:

- Mary Seacole

- Mabel Keaton Staupers

- Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail

- Hazel Johnson-Brown

- Ruby Bradley

- Walt Whitman

- Dorothea Dix

- Mary Eliza Mahoney

Find Nursing Roles

Nurses can be everyday activists in a variety of roles. If you’re inspired by the works of Susie King Taylor, and you’d like to learn more about opportunities in your area, sign up for nursing job notifications.