Using an Improved Pain Scale for Your Facility: Overview

Measuring pain is an important way to assess how patients are responding to treatments. For decades, pain scales have been used to help monitor changes in pain levels and severity. But since pain can be a very subjective experience, health experts have often questioned whether there’s a need for an improved pain scale or better implementation practices.

Various pain scales have been developed over the years, and using one that’s best suited to your patient population is key. In this guide, we’ll provide an overview of validated pain scales, discuss newer developments, and provide tips on how to improve use of these tools in practice.

What Is a Pain Scale?

Healthcare providers use a variety of measurement tools to quantify or qualify different aspects of patient pain, such as duration, intensity, or tolerability. Pain scales in particular are unidimensional tools that patients use to self-report their pain levels in care situations requiring swift assessment.

For example, nurses often ask patients to rate their pain on a scale of 1 to 10 before administering “as-needed” pain medications like Advil. This allows them to quickly gauge whether a patient needs medications, or if their pain levels have improved from the last dose.

Pain scales are designed to be quick measurement tools, and it’s important to differentiate them from longer multidimensional assessments, such as the McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ). These assessments are used in scenarios where a more comprehensive pain evaluation is required. In this guide, we’ll focus on unidimensional pain scales.

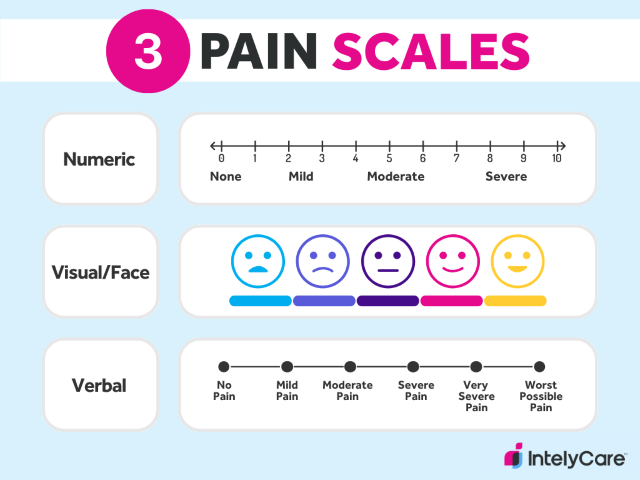

The 3 Main Types of Pain Scales

While many different variations of pain scales have been developed over the years, they generally fall under three broad categories. Here’s an overview of these categories, the pros and cons of each, and some common pain scale examples.

1. Numeric Pain Rating Scales

Numeric pain rating scales display numbers that patients use to “score” the level of pain that they’re feeling. The most commonly administered and validated tool under this category is the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), which asks patients to rate their pain intensity on a scale of 0 to 10 — with 0 meaning no pain and 10 meaning the most severe pain that a patient can feel.

Another example is the Functional Pain Scale (FPS), which alternatively asks patients to rate their pain tolerability. This tool uses a scale of 0 to 5, with 0 indicating no pain and 5 being the most intolerable pain.

| Quick to administer, score, and complete

Can be administered verbally or in writing, increasing its accessibility |

Numbers can mean different things to different patients

Patients may worry about accurately “scoring” their pain |

2. Visual or Face Pain Scales

Visual/face rating scales typically have pictures or a graphic continuum that patients can use to rate their pain. The most widely used tool in this category is the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), which is a horizontal pain scale with descriptions at each end of a line. The left end signifies “no pain” while the right end signifies “severe pain.” Patients are tasked with marking the general area on the line that best represents their pain level.

Additionally, the Wong-Baker FACES Scale is a visual pain scale chart developed for use with children. This tool displays a range of faces, from a happy face (no pain) to a crying face (worst pain), and patients can point to the face that represents how they’re feeling.

| Provides patients with a wider and more flexible continuum to rate their pain

Well-suited for patients who communicate more easily with visual references |

May be confusing if patients don’t resonate with pictures on the scale

May take more time to describe how patients should use these scales |

3. Verbal Rating Scales

Verbal rating scales provide specific adjectives that patients can choose from to describe their pain level. The most popularly used scale under this category — appropriately named the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) — typically uses five descriptors: no pain, mild, moderate, severe, and very severe.

| Easy for patients to use and understand

Quick for providers to describe and administer |

Difficult to use if there are language barriers between patients and providers

Fewer categories makes it difficult to gauge smaller changes in pain levels |

Is There an Improved Pain Scale?

Traditional pain scales can serve as helpful tools in certain clinical settings, but they’ve also shown to be somewhat meaningless or misleading in others. For example, some health experts believe that poor pain management in veteran and military patients is partially tied to inaccurate pain assessments.

The Defense and Veterans Pain Rating Scale (DVPRS) was created in 2010 in light of concerns that simple measures of pain intensity/tolerability didn’t accurately capture the complexity of chronic pain in these populations. This includes a numbered rating system with more functional word descriptors in addition to pictures of faces to represent pain levels. By enhancing and combining different elements of traditional pain scales, the DVPRS allows for more comprehensive assessments in military and veteran personnel.

So, while there are population-specific adaptations of traditional tools, there’s no universally-endorsed improved pain scale that’s right for all settings. It’s important that facilities adopt pain scales that have been well-researched and validated in context to their specific patients’ needs.

General Tips for Improved Pain Scale Usage

There may not be a one-size-fits-all pain scale, but there are ways to maximize the utility of existing tools in practice. Follow these three tips to improve pain scale usage at your facility.

1. Select Patient-Centered Pain Scales

Beyond using validated tools, it’s important to select ones that are best suited for your patient population. Be sure to account for factors such as a patient’s age, reading level, language, and goals for treatment.

2. Ensure Patient Understanding

Since pain scales are self-report tools, patients must be thoroughly educated on how to use them on first administration. Beyond describing what the tool is, be sure to explain what each score, number, or visual means so that patients accurately rate their pain levels.

3. Provide Staff Training

Provide pain scale training to staff to support consistency in how scores are interpreted and ensure they’re on the same page about how these tools should be used. For improved pain scale accuracy, it’s important that staff conduct meaningful assessments that inform appropriate care decisions.

Discover More Ways to Enhance the Patient Experience

Adopting improved pain scale practices can inform more accurate treatment decisions and foster positive patient outcomes. Don’t miss out on IntelyCare’s other free healthcare tips and strategies to enhance patient care, delivered straight to your inbox.