5 Famous Black Nurses Who Changed the Profession

Black female nurses are an essential part of the past, present, and future of nursing. Supporting and uplifting Black women in nursing is critical, not only to right historical imbalances but also to meet the needs of a healthcare system that serves everyone.

Diversity in nursing directly impacts the quality of patient care. But while nearly 14% of the American population is Black, only 6.3% of nurses are. Racism in medicine remains a pervasive problem today, affecting patients and providers. As populations grow increasingly diverse, so must the nursing workforce and its leaders.

You’ve likely heard of Florence Nightingale and Clara Barton, but there are many famous Black nurses who have helped evolve the profession as well, often without the recognition they deserve. Let’s explore five Black nurses in history who have made an impact on the timeline of nursing.

5 Famous Black Nurses to Know About

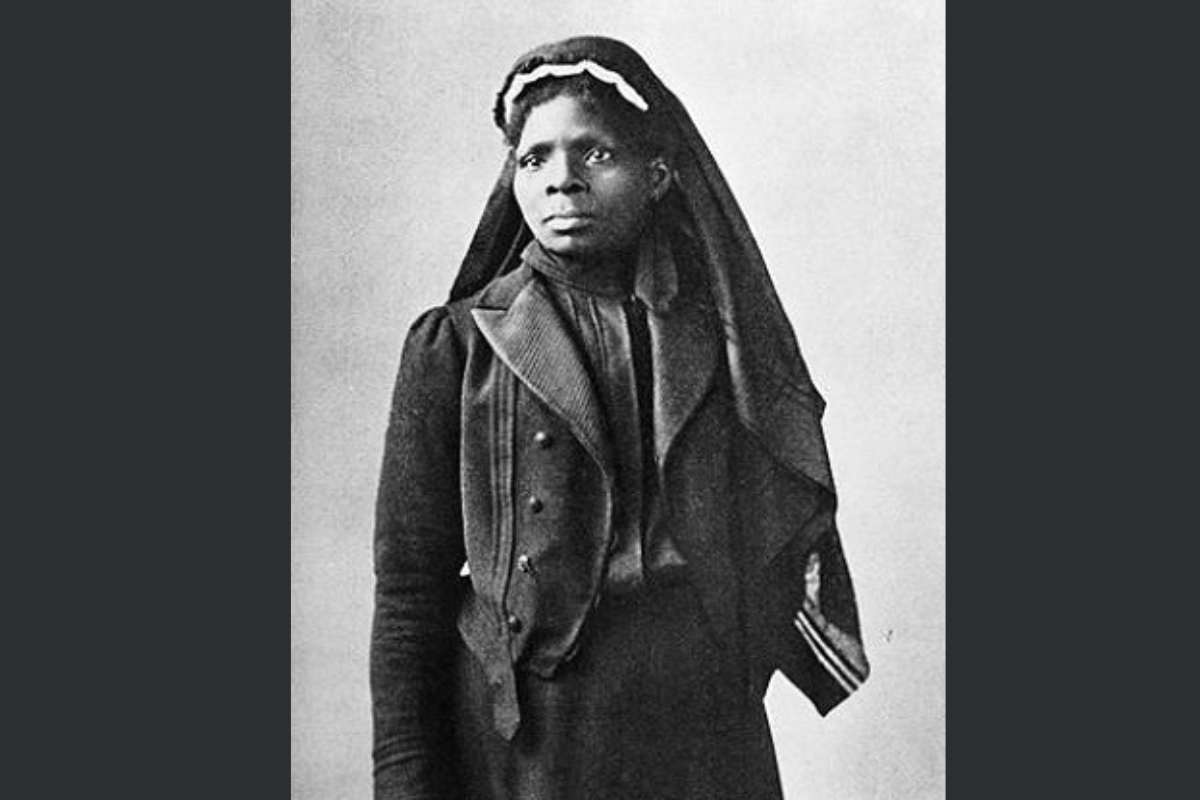

Mary Seacole (1805–1881)

A Jamaican-born nurse and businesswoman, Mary Seacole traveled to the Crimean War front independently after her offer to join Florence Nightingale’s nursing team was rejected, likely due to racial bias. Undeterred, Seacole established her own ward near the battlefield, where she treated wounded soldiers, offered comfort through meals, and provided rest amidst the chaos.

Seacole’s approach combined traditional herbal remedies learned from her mother, known as a “doctress”, with emerging Western medical techniques she picked up in Jamaica, Cuba, and England. Her efforts eased physical suffering and lifted morale, earning her the nickname “Mother Seacole” from those she cared for.

Despite facing financial hardship after the war, Seacole wrote a best-selling autobiography, Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, which was the first memoir by a Black woman in Britain. She was later celebrated through fundraising efforts led by military personnel and officials, and in 2016, a statue was unveiled in her honor at St Thomas’ Hospital in London.

Seacole’s legacy shows that nursing extends beyond institutional boundaries, and that compassion, adaptability, and ingenuity are essential qualities of patient-focused care.

Harriet Tubman (1822–1913)

Best known for her heroic efforts guiding enslaved people to freedom on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman also served as a nurse during the Civil War. Between 1862 and 1865, Tubman lived in Union-occupied Port Royal, South Carolina, where she provided medical care to newly freed people and wounded Black soldiers. With limited supplies, she relied on traditional herbal medicine, using remedies like water lily and cranesbill to treat dysentery.

Tubman also worked as a scout and spy for the Union Army. In one of her most significant missions, she helped plan and lead the Combahee Ferry Raid in June 1863 alongside Colonel James Montgomery. Tubman navigated Union boats through mine-filled waters and helped rescue more than 750 enslaved people. Her bravery and tactical knowledge helped the mission succeed and made her the first American woman to lead a military raid.

After the war, Tubman became a women’s voting advocate and opened a nursing facility of her own, where she died in 1913. Tubman’s work as a nurse, healer, and leader shows that nursing is more than clinical care and can also be a powerful tool for justice and liberation.

Mary Eliza Mahoney (1845–1926)

The first Black female nurse to be formally trained and licensed in the U.S. was Mary Eliza Mahoney from Boston, Massachusetts. Educated at one of the first integrated schools in the country, Mahoney began working at the New England Hospital for Women and Children in her teens and attended nursing school there. Of 42 students who entered the demanding program, Mahoney was one of only four to graduate.

During her clinical career, Mahoney was known for her patient, efficient bedside manner, serving patients and their families in private duty nursing. While nurses in these settings were often treated as household staff at the time, Mahoney demanded respect by eating meals with her patients rather than being sequestered in servants’ quarters.

Mahoney was a pioneer and an advocate for equity in nursing and patient care. In 1908, she cofounded the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN), a stepping stone toward the integration of Black female nurses into nursing education and practice. Later in her career, she became the director of the Howard Colored Orphanage Asylum in Long Island. In 1920, she was one of the first women to vote in Boston.

Mahoney’s impact lives on in awards and memorials dedicated to her incredible career. The American Nurses Association awards the Mary Mahoney Award to nurses who promote integration in the profession. She is also in the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Her life’s work reminds us that professional excellence and social justice are inseparable in nursing’s journey forward.

Susie King Taylor (1848–1912)

Susie King Taylor was a nurse, teacher, and one of the earliest Black women to serve as an Army nurse during the American Civil War. Born into slavery in 1848 in Georgia, Taylor secretly learned to read and write as a child — an illegal act at the time — attending covert schools run by Black women in the community. After escaping slavery with her family in 1862, she joined Union forces stationed on St. Simons Island, where she began teaching formerly enslaved children and adults how to read and write.

While serving with one of the first all-Black Union regiments, Taylor worked as an informal nurse, laundress, and munitions manager. She cared for sick and wounded soldiers, assisted during outbreaks of smallpox and dysentery, and supported men recovering from combat injuries.

After the war, Taylor continued her commitment to education and community, opening schools for Black children. She also worked as a housekeeper, but her interest in the “boys in blue” remained. In 1902, she published Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33rd United States Colored Troops, making her one of the first Black women to publish a memoir about the Civil War. The book offers a rare firsthand account of the experiences of Black soldiers, nurses, and educators during and after the conflict.

Although she never received formal recognition or compensation for her nursing work, Susie King Taylor’s legacy endures as a foundational figure in Black nursing history. Her life reflects nursing’s roots in service, resilience, and justice, and shows that long before the profession was formalized, Black women were already doing its most essential work.

Mabel Keaton Staupers (1890–1989)

Born in Barbados, Mabel Keaton Staupers was a nurse and advocate whose leadership helped dismantle racial barriers in American nursing. After immigrating to New York City as a child, she graduated with honors from the Freedmen’s Hospital School of Nursing in Washington, DC, and spent her early career as a private duty nurse. Alongside two Black physicians, Staupers helped establish the Booker T. Washington Sanitarium in Harlem, one of the few inpatient facilities where Black physicians could treat Black patients.

In 1934, Staupers became a leading voice for professional equity when she was appointed executive secretary of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN). In this role, she organized nurses across the country to challenge discriminatory policies that barred qualified Black nurses from military service and excluded them from many professional organizations.

During World War II, Staupers mounted a campaign to integrate Black nurses into the U.S. military. With persistent advocacy and support from public figures such as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, she helped secure the Army’s and Navy’s acceptance of Black nurses by 1945. Her work also contributed directly to the American Nurses Association’s decision to fully integrate in 1948, leading to the dissolution of the NACGN.

Staupers was awarded the NAACP’s prestigious Spingarn Medal in 1951 and was later inducted into the ANA Hall of Fame. She documented her experiences in No Time for Prejudice: A Story of the Integration of Negroes in Nursing in the United States, preserving her legacy for future generations. Staupers’ life work is an impressive testament to the essential role nurses play in pushing the profession — and society — towards greater justice.

Explore the Lives of More Black Nurses in History

Nursing Jobs for Changemakers

These famous Black nurses have made the nursing profession better. Inspired? If you’re seeking a new work setting, learn more about how we can send you personalized job notifications tailored to your preferences.