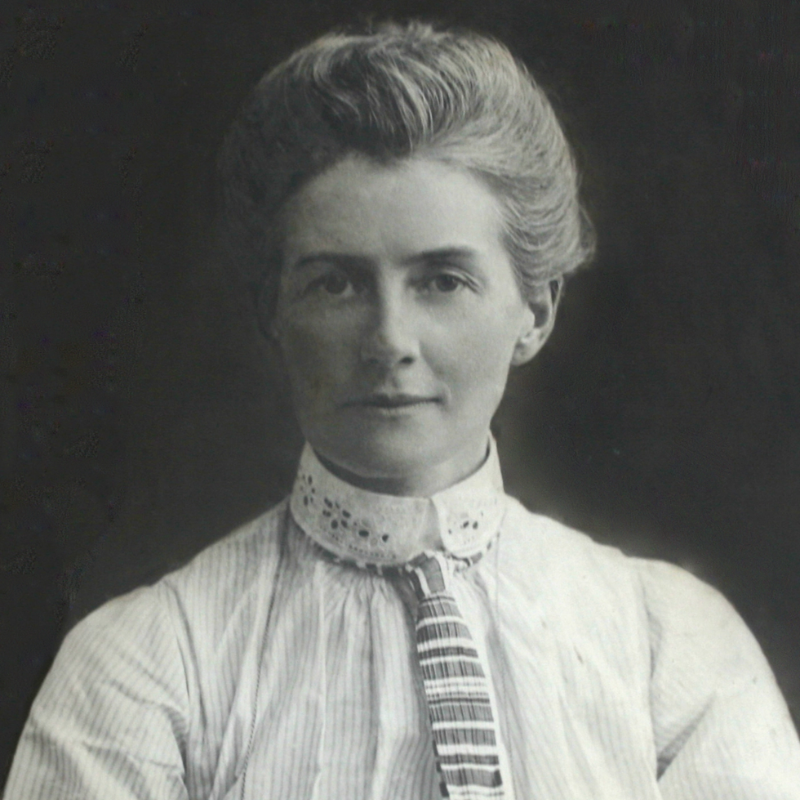

Who Was Edith Cavell? Nurse Biography and Legacy

“Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone” — these were the final words of Edith Cavell, a British nurse working in German-occupied Belgium during World War I. She treated wounded soldiers, regardless of the flag on their uniform, and quietly helped Allied soldiers and civilians escape occupied Belgium into neutral Holland. It was these actions that led to her arrest and, ultimately, her execution in 1915. But instead of silencing her, Cavell’s death turned her into a global symbol of courage and conscience.

So, who was this noteworthy woman? And what made her a remarkable figure in nursing history and beyond? Read on for a deep dive into Edith Cavell’s life and legacy.

Image source: EdithCavell.org

Edith Cavell: Interesting Facts

- Full name: Edith Louisa Cavell

- Birth: December 4, 1865, in Swardeston, Norfolk, England

- Education: Trained as a nurse at the London Hospital at Whitechapel

- Occupation: Nurse and humanitarian

- Key accomplishments: Pioneered modern nursing practices in Belgium; cared for wounded soldiers; organized a secret network to help Allied soldiers and civilians escape occupied Belgium

- Humanitarian impact: Risked her life to provide impartial care during wartime and inspired reforms in international law and nursing ethics after her execution by German forces

Edith Cavell: Biography

1. Early Life

Edith Cavell was born on December 4, 1865, in the quiet village of Swardeston, Norfolk. Her father, Reverend Frederick Cavell, was the local vicar, deeply involved in helping the community. Though the family wasn’t wealthy, they often shared meals with those who had none. Watching her parents lead by example, Cavell learned to care for others.

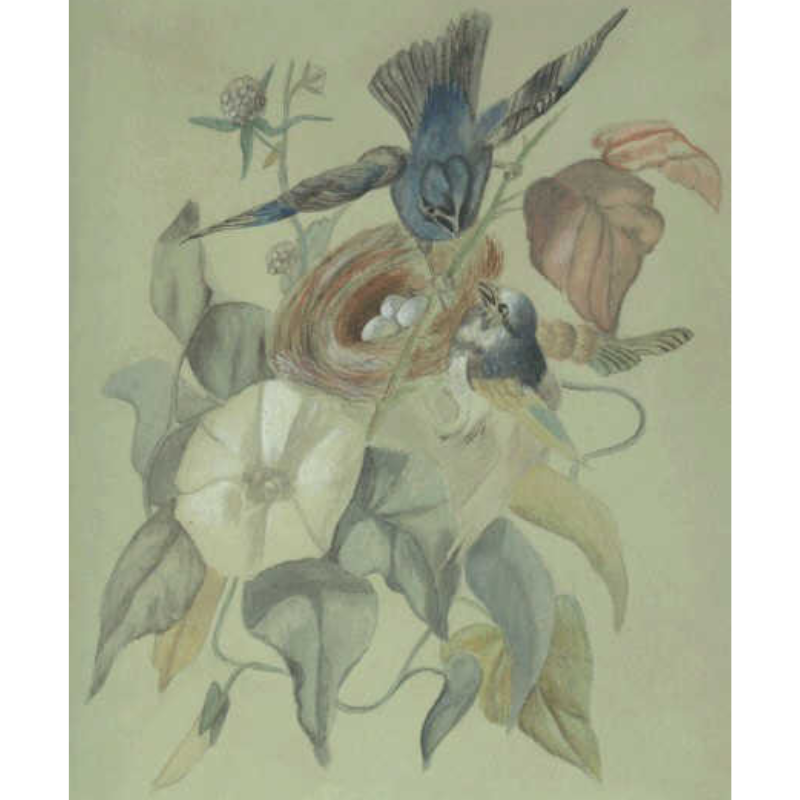

Cavell’s early education was mostly at home, but in 1881 she briefly attended Norwich High School, then went to boarding schools, including St. Margaret’s in Kensington (for poor clergy families). Excelling in French, art, and music, she also loved ice skating, flowers, and nature, and was known for her warmth and kindness to animals and children.

A drawing by Edith Cavell. Image source: EdithCavell.org

One of Cavell’s early accomplishments was raising £300 to build a new Sunday school room next to their family’s vicarage. She and her sister painted and sold cards to help fund it, creating a space for village children to gather for lessons and stories, where Cavell also volunteered as a teacher.

As a young woman, Cavell worked as a governess for families in Essex and Norfolk before taking a position in Brussels in 1890, thanks to her knowledge of French. Her travels to Austria and Bavaria inspired her growing interest in nursing, and she even donated part of a small inheritance to a hospital she visited there.

2. Nursing Career

After five years working as a governess in Brussels, Edith Cavell returned home in 1895 to care for her sick father. Nursing him through his illness sparked a calling she couldn’t ignore. Soon after, she started helping out at Fountains Fever Hospital in Tooting, and in 1896, at age 30, she was accepted for formal training at the London Hospital in Whitechapel under the strict and highly respected matron Eva Lückes.

Though the training was demanding — with long hours, strict discipline, and modest pay — Cavell persevered. During the 1897 typhoid outbreak in Maidstone, she was one of six nurses sent to help. Out of 1,700 infected, only 132 died — an outcome that earned Cavell the Maidstone Medal, the only official medal she received in her lifetime.

While she didn’t always win over her supervisors — Miss Lückes once noted that Cavell had “plenty of capacity for her work, when she chose to exert herself” but was poor on punctuality — her dedication to nursing only deepened over time. She worked in private nursing and took challenging posts at institutions like St. Pancras and Shoreditch Infirmary, where she introduced home visits to follow up with discharged patients — a rare practice at the time.

By 1906, she was stepping in as acting matron in Manchester, filling in for an ill supervisor despite being new to the Queen’s District Nursing system, showing her usual willingness to help where needed.

The following year, she returned to Brussels to care for a young patient of surgeon Dr. Antoine Depage. Impressed by her skill, he soon asked her to lead Belgium’s first professional training school for nurses, L’École Belge d’Infirmières Diplômées. Until then, most nursing care was done by untrained nuns. Cavell’s mission was to change that.

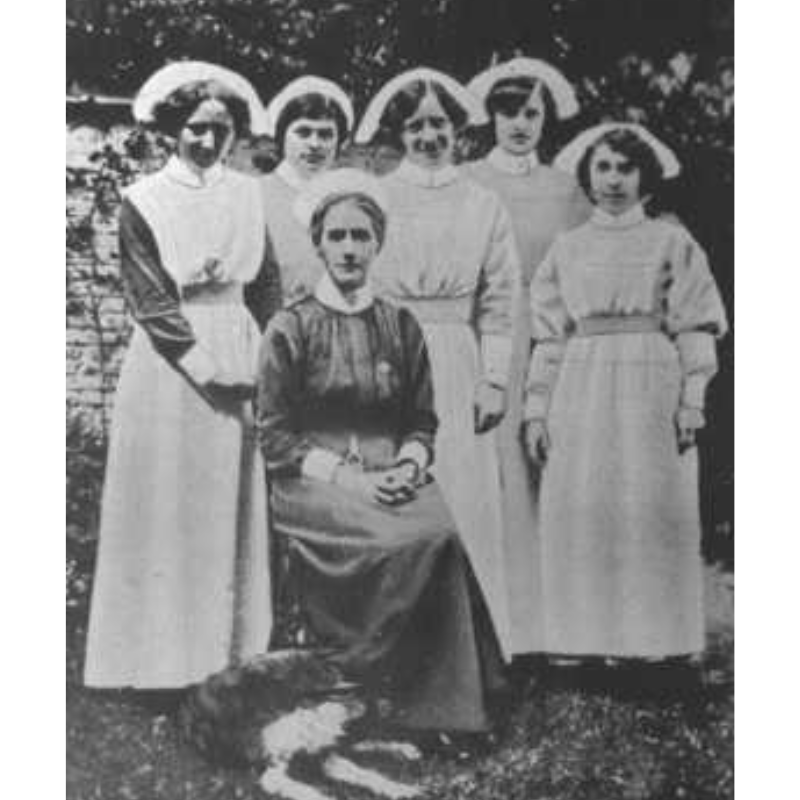

Despite initial resistance — particularly from Belgium’s middle and upper classes who frowned on women working — Cavell threw herself into the task. By 1912, she had trained nurses who were working in three hospitals, two dozen schools, and multiple kindergartens. She also gave regular lectures and quietly continued to care for anyone in need, from struggling patients to stray animals.

Edith with her nurses. Image source: EdithCavell.org

3. Nursing During World War I

In the summer of 1914, Edith Cavell was back in Norfolk when news broke of Germany’s invasion of Belgium. She didn’t hesitate. “At a time like this,” she said, “I am more needed than ever.”

By early August, she had returned to Brussels, firmly instructing her team to care for all wounded soldiers, no matter which side they fought for. Under her lead, the clinic became a Red Cross hospital caring for both Germans and Belgians. However, when Brussels fell, the Germans took control and ordered the hospital to treat only their own troops. Most English nurses were sent home, but Cavell and her assistant, Elizabeth Wilkins, stayed on.

Soon, Cavell’s nursing work turned into something far riskier. As the German army advanced and the Allies retreated, many British and French soldiers were left stranded behind enemy lines. In the autumn of 1914, two British soldiers reached Cavell’s training school, and she hid them for two weeks. Word spread, and others followed. With the help of local allies — including the Prince and Princess de Croy and Belgian architect Philippe Baucq — Cavell joined a secret escape network that helped over 200 Allied soldiers and civilians reach neutral Holland.

Her role in the network was dangerous, but to Cavell, saving lives mattered more than rules. “Had I not helped,” she later said, “they would have been shot.” Cavell’s school became a training center and a shelter, where she kept her activities so hidden that even her nurses had no idea what was going on. She understood the risks: Helping enemy soldiers escape was punishable by death. But to her, saving lives was simply the right thing to do.

The betrayal came unexpectedly — a Belgian collaborator, someone Cavell had unknowingly helped, exposed the escape network to the Germans. Soon, two key members were captured, and on August 5, 1915, Cavell was arrested. During interrogation, she admitted it all — that she had sheltered Allied soldiers and helped them escape — and claimed full responsibility in a desperate attempt to shield the others. Her confession sealed her fate.

Though her actions meant death under German law, the quiet cruelty of her execution stunned the world. Appeals from the U.S. and Spain were dismissed. No delay. No mercy. And at dawn on October 12, in the stillness of Brussels, Edith Cavell stood alone — calm, brave, and unarmed — before the rifles.

Cavell’s funeral procession. Image source: The Guardian

Cavell was first buried at the rifle range where she was executed. After the war, her remains were exhumed and returned to England in May 1919. Following a funeral service at Westminster Abbey, she was laid to rest at Life’s Green in Norfolk, beside the Cathedral’s St Saviour’s Chapel. The most famous Edith Cavell memorial stands in London near Trafalgar Square. Other memorials exist in Brussels and at nursing institutions worldwide.

The Edith Cavell statue in Trafalgar Square. Image source: The National WWI Museum and Memorial

Edith Cavell: Last Words

After her arrest in August 1915, Edith Cavell spent 10 weeks in solitary confinement at St. Gilles Prison. Cut off from the world, she faced long interrogations and the threat of death in total isolation. But instead of breaking down, she found peace.

“I thank God for these 10 weeks of quiet,” she wrote. “It has been like a solemn fast from earthly distractions.” She used the time to reflect, pray, and make peace with her fate. To the end, she stayed calm, steady, and true to herself.

The night before her execution, she was visited by the British chaplain Reverend Stirling Gahan. “I have seen death so often,” she told him,“that it is not strange or fearful to me.” When he called her a heroine and a martyr, she replied simply: “Don’t think of me like that: Think of me simply as a nurse who tried to do her duty.”

At dawn on October 12, 1915, Edith Cavell faced the firing squad at the Tir Nationale — not with hatred, but with grace. Her final words live on:

“Standing as I do in the light of God and eternity, I have realized that patriotism is not enough: I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

After Cavell’s death, the nurses she had trained discovered a letter she had written to them the night before her execution. In it, she offered them comfort and encouragement:

“When better days come, our work will again grow and resume all its power for doing good. I told you in our evening conversations that devotion would bring you true happiness and that the thought that before God you have done your duty well and with a good heart will sustain you in the hard moments of life and in the face of death. I may have been strict, but I have loved you more than you can know.”

Myths Surrounding Cavell’s Death

Edith Cavell’s death quickly became the subject of powerful stories — some inspiring, others exaggerated or simply untrue. Separating fact from fiction is essential to truly understand her courage and the legacy she left behind. Let’s unravel some of the most common myths about her execution.

| Myths | Facts |

|---|---|

| Cavell died with a dramatic last speech condemning the Germans. | Cavell’s final words expressed forgiveness and a lack of hatred, emphasizing duty over patriotism. |

| Cavell was shot with cruelty, fainted, or was finished off by a pistol shot after the firing squad missed. | Reliable witnesses confirm her execution was carried out swiftly and without incident. |

| The firing squad refused to shoot her (or missed intentionally), and one of the soldiers was executed for disobedience. | There is some evidence that a soldier refused to shoot her and may have been punished, but this is not fully verified. |

| Cavell wanted to be remembered as a hero. | Cavell wanted to be remembered simply as a nurse who did her duty. |

| Cavell was naïve about the dangers of helping Allied soldiers escape. | Cavell was fully aware of the risks but chose to act out of conscience and faith. |

| Cavell was a British spy. | The British government denied that Cavell was a spy, but some sensitive information was carried through the network with her help. |

| Cavell’s death had very little impact on the world. | Her death caused international outrage and helped turn opinion against Germany, influencing the U.S. entry into WWI. |

Edith Cavell: Nurse Beyond Duty

Edith Cavell’s legacy is often remembered in dramatic headlines and heroic myths, but the true story is far more nuanced. As a nurse, educator, and humanitarian, she quietly transformed nursing in Belgium, influenced international wartime law, and challenged outdated beliefs about women. Here’s a closer look at her lasting impact:

- Revolutionized nursing in Belgium: Established Belgium’s first professional nursing school, elevating nursing from informal care to a respected, evidence-based profession.

- Defined nursing: Provided impartial care to all wounded people, demonstrating that the core nursing ethical principles transcend politics and conflicts.

- Saved over 200 lives: Coordinated a secret network that helped Allied soldiers and civilians escape occupied Belgium.

- Challenged gender norms: Broke societal stereotypes by leading in a male-dominated field, inspiring future generations of women in medicine and beyond.

- Influenced international law: Her execution caused global outrage and contributed to the development of stronger protections for medical personnel during war.

- Embodied morality: Lived out values taught by her priest father — showing that true devotion is measured not in words, but in actions.

Edith Cavell: Famous Quotes

Inspiring sayings from nurses like Cavell offer rare insights into the true spirit of caregiving. These quotes show what fueled Cavell’s courage and compassion:

- “I can’t stop while there are lives to be saved.”

- “The everyday kindness of the back roads more than makes up for the acts of greed in the headlines.”

- “I must have less need to be neat and more desire to save.”

- “Fear is not one good reason for staying at home.”

- “I believe God will yet raise up a mighty nation that shall be a blessing to all mankind.”

- “I believe that patriotism will not be the highest virtue of mankind.”

- “To work for God is the only satisfactory life.”

- “I realize that love and sacrifice are behind all true greatness.”

- “Ask Father Gahan to tell my loved ones later on that my soul, as I believe, is safe, and that I am glad to die for my country.”

Quotes About Edith Cavell

Those who knew Cavell personally spoke of her quiet strength, fierce intelligence, and deep kindness. These tributes offer a glimpse of the real Edith — the mentor, leader, and friend:

- “Edith was one of the kindest and gentlest women I have ever known … never in a hurry, always ready to do a right action — a quiet, modest, God-fearing woman” — Rev. Philip Stocks

- “When the news reached us today, there was not a dry eye among those who knew her. Many a shabbily dressed caller today asked, ‘Is it true?’ remembering the many kindnesses she had done for them or their children … A splendid teacher, a very capable organizer, and a zealous worker. She brought to her work an extremely acute intelligence …” — Unnamed colleague

- “She received me coldly at first, very reserved and sure of herself. She is tall and slight, wears her blue nurse’s dress, her grey hair gathered under the white cap; her big eyes show sympathy and intelligence.” — The Princess de Croy

- “She was the best friend I ever had.” — Lance Corporal Arthur Wood

- “A frail, delicate-appearing little woman. Her hair was greying and she looked more than her 45 years owing to years of dedicated hard work.” — Sister Elizabeth Wilkins

Works Inspired by Edith Cavell

Cavell’s story didn’t end in 1915. It continues through the pieces created in her honor, helping the next generation discover what it means to live with purpose. Check out some prominent works inspired by Cavell’s life:

- The Cavell Case: A silent film based on Cavell’s life

- Nurse Edith Cavell: A film directed by British director Herbert Wilcox

- “The Untold Story of Edith Cavell”: An episode from a BBC radio documentary series

- Edith Cavell Medical Centre: A medical institution in Brussels, Belgium

- Cavell: A UK-based charity supporting nurses, midwives, and nursing associates suffering personal or financial hardship

- Numerous books and biographies

Other Famous Nurses

Want to read more fascinating stories about the lives and legacies of other famous nurses? Check out our articles on other nursing pioneers:

- Clara Barton

- Dorothea Orem

- Florence Nightingale

- Harriet Tubman

- Lucy Higgs Nichols

- Mary Seacole

- Susie Walking Bear Yellowtail

- Walt Whitman

Ready to Start an Impactful Nursing Career?

Inspired by greats like Edith Cavell? At IntelyCare, we believe you can follow your passion, stay true to your values, and change lives. Get access to personalized job matching to discover goals tailored to what matters most to you.